Reviews / A spellbinding story that reinforces the personal impact of war

Local history teacher Jon Sandison reviews Jonathan Wills’ book on his uncle Davie and his time as a prisoner of war

“Do we need another book on World War Two?” author Jonathan Wills reflected at the launch of his latest book Uncle Davie’s Red Cross Blanket: The Story of David J. Slater, a Shetland PoW in Nazi occupied Poland, 1940-1945.

The answer going through the mind of the large group who attended the Shetland Library event, before the author himself even answered his own question, was without question a resounding ‘yes’. Not least, it should be added, we do need a book such as this.

All photos: Courtesy of Jonathan Wills archive

Shetland needs more books telling the story of our islands, and its connections to both wars, that expand further the written record and understanding of these testing times and how Shetland, and its people were affected and responded.

Moreover, the 100th anniversary of World War Two isn’t really that far away, and this book is a testament to these times. Moreover, there has been little focus on the Shetland prisoners of war. That in itself is a vital facet of this book.

The book title is the basis of the story; a blanket which the author’s uncle, Davie Slater, had while a PoW during World War Two. That, and his letters and postcards home, drive a spellbinding story, so wonderfully written.

From the outset, a connection to a blanket reminds us that ‘sources’ are not just of the written variety, but also can be so personal in nature. The blanket was passed on to the author whilst staying in a Bressay croft and undertaking his post-graduate degree in 1969.

Become a member of Shetland News

This book therefore really reinforces the personal impact of war, sharing the important local story of the local territorial’s departure in 1939 alongside the very personal experience Davie Slater. He was one of 10,000 men of the 51st Highland division who were taken prisoner at St Valery-en-Caux in June 1940 following the fall of Dunkirk.

An initial engaging narrative is shared of Davie’s younger life in Scalloway and then his recollections of departing for war. All this helps us to understand the man whose story is to be told.

Throughout, the book provides a dual purpose of, first and foremost, providing a fascinating piece of family and social history, while – at the same time – giving a military history.

The author intermeshes his uncle’s letters to his father and sister in Scalloway. He wrote more than 200 postcards and letters to them. Each personal account and contact from Davie resonates his experience of war and reminds us ultimately that it is individual stories of people who were exposed to the wartime period that reverberate.

Their endurance forever makes us ponder and reflect upon what this special generation went though. Davie’s story is another important piece of that jigsaw.

Of course, we will never really know, and thank goodness for that. But we can but try to understand. This book helps us to do just that.

Davie’s first letter correspondence following his capture at St Valery got to me. Almost apologetic in tone, a measure of his own thoughts. It is hard to comprehend the thoughts of those at home upon reading this, knowing he was safe, if captured:

Dear Dad and Nina,

Just a short note to let you know that I am safe and well. I know you must be terrible worried at not hearing from me, but you will likely have been informed that we were captured a fortnight ago so that way I have had no chance to write. Will you please not be annoyed as I am alright and so far along with the boys I know. Smithie and Houston and one or two of the other boys are all sticking in together. I cannot tell you anything about it yet or where to write, but that will not matter meantime as everything is ok.

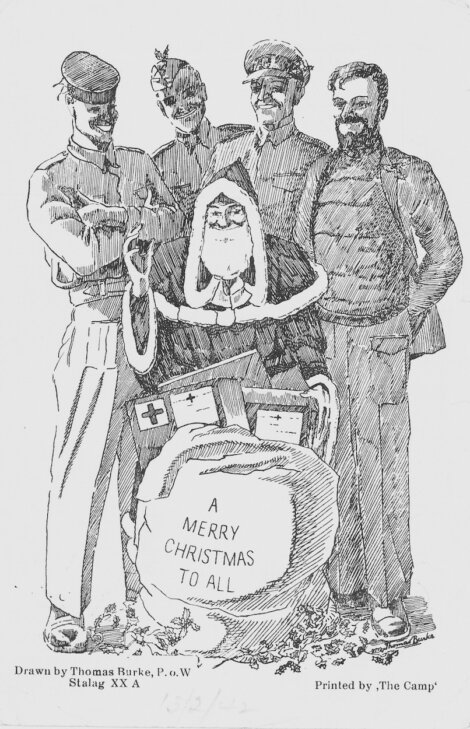

Throughout Davie’s story, the book brings you right to the forefront of his experiences following becoming a prisoner. The unfolding fascinating story gives insight into the gruelling forced march of 800 miles which the men made, and then settlement into the Stalag XXA camp.

Other key themes include Davie’s experience working on the farms outside of the camp containment, as well as how camp Kommandants being held to account.

A further ominous reminder to the reader was that ultimately once the war was over, for these prisoners it was not over! With the Red Army advancing from the East, there was a further forced march west before liberation.

The story comes full circle with the last chapter focussing on Davie’s post-war years, marriage and daily work in Lerwick as a foreman on Victoria Pier. The book is methodically researched.

The book combines historiography and war diaries with newspaper and national archives records and sets this all against the wider context of the war.

Central to the book are the PoW camp inspection reports on Stalag XXA by the International Red Cross which give further insight into Davie’s experiences as a prisoner.

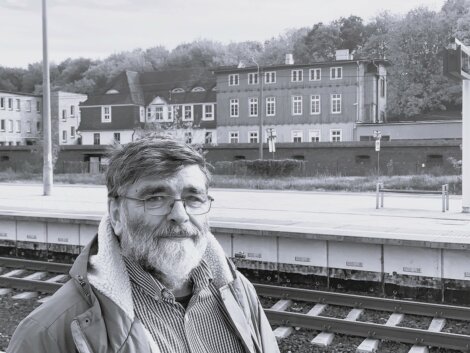

The author has followed in his uncle’s footsteps by visiting his route. This adds further weight.

Adjacent to all of this are maps linked to the story, and many fascinating archive images, personal family photos, and wonderful maps all meticulously arranged and sorted by the author. All of this cements together the story he tells.

Uncle Davie’s Red Cross Blanket: The Story of David J. Slater, a Shetland PoW in Nazi occupied Poland, 1940-1945. Priced £20, it is available via Amazon here.

Become a member of Shetland News

Shetland News is asking its readers to consider paying for membership to get additional perks:

- Removal of third-party ads;

- Bookmark posts to read later;

- Exclusive curated weekly newsletter;

- Hide membership messages;

- Comments open for discussion.

If you appreciate what we do and feel strongly about impartial local journalism, then please become a member of Shetland News by either making a single payment, or setting up a monthly, quarterly or yearly subscription.