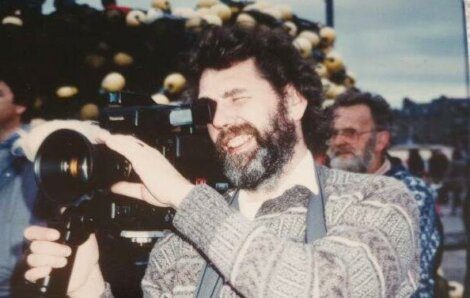

Tributes / John H. Waters (1943 – 2023): a generous and remarkable person we shall miss very much

An appreciation by Jonathan Wills

THE death of my old friend and colleague John Waters on 17 August did not come as a surprise, least of all to him. As he’d cheerfully remarked only the previous week, every morning he woke up he was astonished to find himself still here, in his eightieth year.

Although he made light of his infirmities, over the past year he’d found it more and more difficult and exhausting just to breathe. There had been several alarming medical emergencies, all of which he played down or joked about, but he did reluctantly agree to use his oxygen mask and carry an alarm button.

He kept working until the end, the last BBC job for his Norfilm company being some spectacular drone footage of the Tall Ships Races at Lerwick in July.

John had several overlapping careers. Some of them only started after he’d officially retired from the BBC. At various times he was a radio and TV transmitter engineer, radio studio engineer, press photographer, freelance video news cameraman, video editor, drone pilot, maker of radio-controlled model boats, planes and trains and, among other things, designer of a remotely controlled underwater viewing system for a wildlife tour boat and a solar- and wind-powered 12-volt electrical installation for an off-grid croft bothy.

It was sometimes hard to distinguish between John’s work and his hobbies. His generosity with his time and expertise for the benefit of his many friends was legendary, and usually unpaid.

John H. Waters was born in Sutton Coldfield, Warwickshire, in 1943, the oldest of Dorothy and Trevor Waters’ three children. After Bishop Vesey Grammar School he joined the BBC as an apprentice transmitter engineer. His work took him from the local transmitter at Sutton Coldfield to Daventry, north of London, and later to Caithness.

In 1969, when the BBC added BBC2 to their TV transmitter on the Ward of Bressay, he came to Shetland, where his boss Derri Cameron became a lifelong friend. Derri died earlier this year and John was greatly distressed that he wasn’t well enough to attend the funeral.

In 1977 John and Derri were asked to keep an eye on the technical side of the new BBC Radio Shetland studio in Harbour Street, Lerwick. Instead of buying an off-the-peg control desk for Radio Shetland the BBC had set up a technical committee which designed and built its own. It cost a fortune and didn’t work very well at first, which is why John was twiddling an insulated screwdriver and a pair of pliers underneath my chair as we went live on air for the first time. Such experiences build mutual trust…

Radio Shetland depended on regular help from John but never more so than in 1980 when a Spanish tug grounded on the submarine cable that carried our signal from the Lerwick studio across Bressay Sound to the Ward Hill transmitter. We were off air.

Not for long, though: it would take weeks to get a cable-laying ship north but within days John and his mates had sourced some VHF signal kit in BBC Scotland’s Glasgow engineering stores; soon they were on the roof of our Harbour Street studio, strapping a microwave dish to the chimneys; this they aligned (by sight, using binoculars) with another dish lashed to the Bressay transmitter mast. Within a week we had a broadcastable signal again; it hummed a bit, but nobody noticed. We were back on air.

Regular visits to the Ward Hill meant that John was a well-known figure in Bressay, where he knew all the island ‘characters’ and revelled in humorous stories of their scrapes and adventures. Before the car ferry service started in 1974 he crossed the sound in the Brenda and other small passenger ferries, often in poor weather, and then drove the battered BBC Land Rover up the steep track to the transmitter. Coming back down the hill could be quite exciting if the brakes were faulty.

When John took early retirement from BBC Transmitters in 1997, they sent him on a pre-retirement course, which he found quite hilarious. He had no need of advice on how to occupy himself in retirement and said he was already almost too busy with other work to attend the course. For example, for many years he serviced the SIBC transmitter, also on the Ward of Bressay, for his friend Ian Anderson.

John always had the air of an eccentric amateur enthusiast and would jocularly insist that no technical problem was ‘so serious as to merit consulting the instruction manual’, but in fact he was a meticulous and ingenious electronic engineer who took his work seriously, analysed problems systematically and usually knew exactly what he was doing or, if he didn’t, would quickly find out.

His extra-curricular activities included helping friends with their model boats and radio-controlled aircraft, where his professional skills came in very handy, as they did when I started Seabirds-and-Seals wildlife boat tours around Noss in 1992.

John was helpful far beyond the calls of friendship, fixing up the public address system on the first Dunter and, when I started underwater viewing with Dunter II in the year 2000, designing and building from scratch a video display system that worked off the boat’s 12 volt batteries. When we launched Dunter III in 2003 it was again John who devised the underwater video system, fitted, wired and tested the equipment, and only very occasionally used a bad word.

John often had suggestions for improving our operations. For example, he discovered that ordinary car park security cameras costing a few hundred pounds each were waterproof down to 10 metres, which was all we needed to show passengers the submarine life of The Orkneyman’s Cave. Some of his ideas were more zany: now, alas, we shall never see the radio-controlled, life-sized model of a Great Auk which, he speculated, would do wonders for the eco-tourism trade if launched at Twageos and steered past Dennis Coutts’ house.

His model-making skills were remarkable. Shortly before his death, John completed an extraordinarily detailed scale model of a World War II Spitfire fighter, to stand on his mantelpiece at 1 Andrewstown Terrace alongside an equally fine model of an ME262, the world’s first jet fighter.

In the garage, still unfinished, was a working model of a Welsh quarry railway, complete with miniature locos named ‘Tamar’ and ‘Beenie’ which, although electric, made realistic steam chuffing noises as they trundled along.

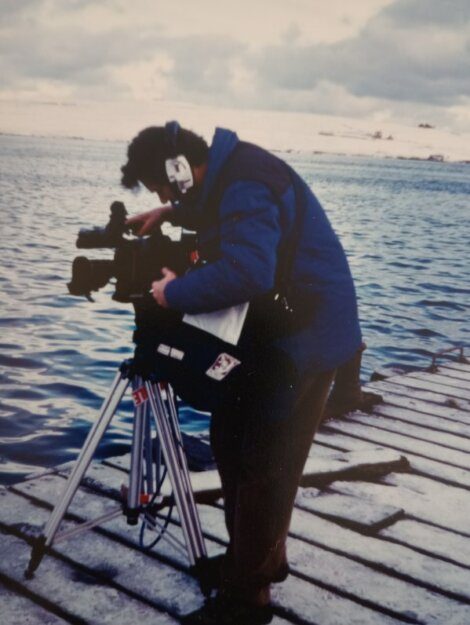

John had already re-trained as a TV film cameraman when one of the biggest news stories of his career broke on the morning of 5 January 1993. The American-owned tanker Braer broke down in the Fair Isle Channel and drifted before a southerly storm force 11 towards the southern tip of Shetland.

She had 84,700 tonnes of crude aboard and at 11:13am the huge tanker grounded and began to spill oil. This may have been the first time a tanker had been wrecked in front of a TV camera. John recorded the whole event on video, despite his tripod and camera almost blowing away. It was an extremely spectacular wreck, exhaustively covered by TV, radio and newspapers from all over the world. John’s grainy but surprisingly unshaky BBC footage scooped them all.

A couple of years later, on Christmas morning 1995 the BBC had a problem: it seemed the Bressay transmitter had gone on the blink in a power cut after a blizzard. The standby generator started automatically but all BBC channels were transmitting on low power. Unless it was fixed by 3pm Shetlanders would have very poor reception for the Queen’s Christmas broadcast.

John rang to ask if I would mind ferrying him and two colleagues across the sound. The roads were blocked by snow but they were going to walk up the 742-feet-high hill to see what they could do. I took my boat over to town in a gap between snow showers and landed the intrepid crew on the Bressay pier, where they donned BBC-issue snowshoes and set off to climb through the drifts, lugging a very heavy spare part that was thought to be the solution to the problem.

Some hours later John and his colleagues appeared at our front door, beaming with success and looking like something out of Scott of the Antarctic. We brushed the snow off their survival suits and invited them to share our Christmas dinner, after which I ferried them back to the town…

It was some years later that John, cackling with laughter, explained why the TV transmitter was on low power: when leaving the building some days before, a new member of staff had omitted to press a certain switch. This was because no-one had told him it was there. On that Christmas Day, when John showed him the ‘magic red standby button’ and pressed it, the transmitter immediately sprang back to full power.

Long after he had officially retired from the BBC, John could often be found at Radio Shetland, sitting in as studio engineer for evening programmes, such as Catgut and Ivory, presented by his friends Gussie Angus and Cecil Hughson, for the annual Children in Need marathon show, on other special occasions and to cover staff absences. He was truly a local radio institution. This was in addition to his day jobs taking stills and video for various local news organisations. There was never any thought of proper retirement. He would have found that very dull.

For many years John was also the official videographer for the Lerwick Up Helly Aa guizer jarls, filming the entire festival over several months from start to finish: the galley builders; the ‘boys who made the torches’; lightsome nights in the bunker and the galley shed; all the way through to the Town Hall reception, the torchlit procession, the galley burning and the many, many dances to follow.

Working with Malcolm Younger and other contributors, John spent long hours editing the finished video of each year’s festival and, although no longer a guizer himself and having long foresworn alcohol, he was a much-respected and indispensable member of the Up Helly Aa team.

He had previously been a painter of the galley shields for many years, an activity that his first wife Ruby only just tolerated in their very small house at Greenfield Square.

John was quick to realise the potential of drone footage, not only for Up Helly Aa shots but also for covering news events. As with transmitters and broadcast-quality video cameras, so with drones: he went on a training course and qualified as a Civil Aviation Authority-approved drone pilot.

His flight logbooks and maintenance records were impeccable so he was indignant when the police seized his new drone after it crashed inside the exclusion zone around the fire that destroyed the Moorfield Hotel near Brae in July 2020. He was threatened with serious charges, but it turned out that the cause of the crash was a manufacturing fault in the drone’s battery.

John’s indignation turned to hilarity when the police kept the offending battery so long that the manufacturer and the CAA could no longer identify exactly what had gone wrong. Needless to say, there was no prosecution and John had yet another funny story to tell his pals. There was more fun when two police officers turned up for his last drone mission but only, John said with a delighted chuckle, to admire the lovely views over the Tall Ships that he was getting from just outside Lerwick Port Authority’s very own ‘air exclusion zone’.

John loved a joke (particularly at the expense of pompous officialdom) and revelled in the company of friends who shared his sense of humour. But his life was scarred by sorrow. He was widowed twice. His first wife, Ruby Irvine, died in 1994. He cared for and nursed her devotedly during her long illness. He was a fond stepfather to George Karstein Irvine and step-grandfather to his children.

With his second wife, Betty Sandison, he enjoyed many happy years, becoming a doting stepdad and step-grandad to her family. When Betty’s health failed and they were no longer able to go on camper van trips or fly to his beloved Norway, he again became almost a full-time carer. Betty died in 2017 and John was bereft. But once more his extended family, a wide circle of friends and acquaintances (including the global audience online for his very funny daily newsletter) and his endless curiosity about new technology – and even politics – kept him going as his own health gave way.

Over our last cup of his awful, microwaved coffee, he cheerily confided that his immediate reaction to the arrest of Nicola Sturgeon, whom he much admired, had been to join the Scottish National Party. I was astonished. But then John Waters was an astonishing person. We shall all miss him very much. He will be long remembered.

- John H. Waters, transmitter engineer and TV cameraman, born 6 December 1943 in Sutton Coldfield; died 17 August 2023 in Lerwick.