Letters / An unprecedented mess

Extraordinary. That the brand-new Tory government has been forced, as its first act, to implement a massive, socialist policy, borrowing £150 billion to save energy consumers from destitution, speaks volumes.

UK energy is in an unprecedented mess.

According to the SIC, Shetland bills are double those of the UK, suggesting that, even with the new subsidy, they will still average over £5,000/year.

Some suggest energy-rich Shetland should look after itself, while others fret over volatile diesel fuel prices and low customer density.

However, costs also depend on how installations are designed and run, begging the question, what happens in other, similar island groups?

According to Faroese supplier SEV’s 2021 annual report, 2022 tariffs are unchanged since 2020 and averaging 17.5p per unit, look extremely reasonable versus our 51.8p, heading for 80-90p by April.

SEV is council-owned and regulated by the Electricity Production Commission/Ministry of Industry. Their focus is local, and prices are set to cover costs and provide modest profit to finance improvements.

Using mainly diesel engines plus substantial hydro and wind, they aim to be 100 per cent ‘green energy’ by 2030 and have invested £348 million over the last 10 years.

Hedging (of oil prices, interest rates and dollar exchange rates) with multi-year contracts helps insure customers against the price extremes we are experiencing here.

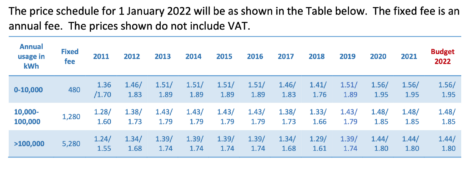

Indeed, their price history (Page 24) shows no sign of volatility due to diesel prices, or anything else, for that matter:

NB [DKK1.0 = £0.116]

At the above tariff, ‘like-for-like’, Faroese consumers should pay around £1200/year, broadly in line with prices in Jersey and the Isle of Man, one third of current UK prices.

Why then could Shetland not manage its own energy supply?

Once the new grid link is commissioned, Lerwick Power Station will be for standby/export only, eliminating diesel cost concerns. Meanwhile, vast renewable energy installations are planned presenting an opportunity to secure long term, affordable supplies, something that, disappointingly, failed to happen with both Sullom Voe Terminal and Shetland Gas Plant.

Surely, it would be absurd to produce energy in Shetland, sell it to mainland companies and then force residents to buy it back at mainland prices set by volatile international gas prices?

Why not negotiate supplies directly from local suppliers, as proposed for the oil and gas industry, avoiding grid link costs and retaining the profits in Shetland?

Shetland Islands Council is seeking increased powers, after all.

A locally-focused strategy and robust arrangements to implement the desired changes are needed, along with regulatory powers to protect customers’ interests which have been trampled under the present regime.

The Faroese model provides an interesting case study as to how that might be achieved in practice.

John Tulloch

Aberdeen