News / Experts warn wind farms should not be built on peatlands

With governments pledging to accelerate the construction of onshore wind power until 2030 to help meet climate targets, scientists call for an urgent review of the policy of building turbines on peatlands. Jen Stout investigates.

THE CLIMATE impact of digging up peat to build wind farms could be greater than thought, scientists are warning – raising questions over turbines in Shetland.

Restoring damaged bogs is increasingly understood to be critical to meeting emissions targets, with more funding announced ahead of COP26 – and experts are calling for an end to wind farms on deep peat.

The 103-turbine Viking Energy wind farm is under construction in central Shetland, while a decision on Energy Isles’ 18-turbine development, on deep peat in Yell, is expected next year.

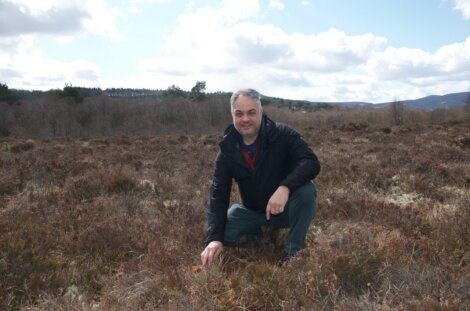

Peatlands, those boggy and waterlogged landscapes covering 10 per cent of the UK land area, and half of Shetland, are the single most important terrestrial carbon store Britain has.

Worldwide, peatlands play a major role in climate regulation, and store at least 550 gigatonnes of carbon, more than twice the carbon stored in all the world’s forests.

Both developers say the green energy generated will pay back carbon losses in less than two years.

But the government calculator used to reach these figures is flawed, according to experts.

Professor Jo Smith, who led the Aberdeen university team which created the spreadsheet tool, said: “The science has moved forward. There’s now more information available that could help reduce two uncertainties: the extent of drainage, and the efficacy of restoration of peatlands.

“Therefore, I’d completely agree with reviewing it.”

Clifton Bain, advisor of the IUCN UK Peatland Programme, said: “There’s a risk that impact is being significantly underestimated. I think that’s highly possible, because it’s based on assumptions, based on outdated data, there’s no oversight of how the model is used.”

One of the biggest factors in bringing down the carbon payback time from decades to just a few years is how far out the bog will drain as a result of tracks and turbine bases being built on it.

Become a member of Shetland News

It can be given as low as 10 metres. In Shetland, Viking Energy’s calculations used ranges between 10 and 50m, while Energy Isles, in Yell, used 17-39m.

According to Dr Guadaneth Chico, who has studied peat bog erosion at wind farms in Spain, the impact varies for every peatland but can be “up to hundreds of metres”.

One of the problems is that drainage is hard to evaluate in the short-term, he added. “It’s a long-term habitat. Restoration tends to be monitored for a few years, then we forget about it. But in three years, it doesn’t change much.”

Promises of restoration are also crucial to reaching a short payback time. Degraded peatland emits greenhouse gases at an extraordinary rate – it’s estimated that Shetland’s peat, in poor condition from centuries of over-grazing, cutting and climate, is emitting hundreds of thousands of tonnes of CO2 equivalent every year.

Viking Energy promise to restore 260 hectares of degraded peatland, while Energy Isles give a net figure of 51 hectares. Around 1,900,000m3 of peat has been excavated from the Viking sites so far, and a spokesperson said all of it is retained for reuse.

But there is considerable uncertainty over whether this works in practice – particularly for pristine peat, as is found on much of the Yell site. The importance of preserving natural blanket bog was reflected in the fact that SEPA initially objected to the Energy Isles proposal on climate grounds. It hasn’t yet responded to the latest proposal, which cut excavated peat volumes by 43per cent.

“The science is not settled on the best ways to restore peatlands and whether it is actually possible in practice,” said Jo Smith.

“If the peat was previously pristine and you drain it, it’s much more difficult to restore to its original condition, because the carbon held in the peat is highly active, and easily decomposed.”

A spokesperson for SSE Renewables said the methods used to restore peatlands were “tried and tested” and overseen by experienced people.

“The overall footprint from Viking infrastructure is more than offset by the work being done to restore historically eroded peatland and the creation of more blanket bog,” the spokesman said.

“Once construction is complete, the process of peatland restoration will continue, using more ‘traditional’ techniques, for example reprofiling peat hags (bare edges) and damming the gullies that guide water away from the blanket bog.”

These were “tried and tested” methods, he said, overseen by people “experienced in Shetland peat restoration”.

Charlotte Healey, Energy Isles project manager, added: “We know the importance of peat, not only from a climate perspective but also as part of the fabric of life in Shetland over the centuries.”

“Earlier this month we held a webinar on this exact topic and were happy to be able to provide information and answer a series of very detailed questions about our plans.”

However, according to Clifton Bain there is no independent scrutiny in place to monitor and evaluate peat restoration.

“The planning system doesn’t have a lot of capacity,” he said, “It doesn’t have trained staff and time to monitor and check.

“There’s a flaw in the system that could allow poor quality restoration, [with] no oversight.”

Oversight is the job of the Scottish Environment Protection Agency (SEPA), and planning departments within local authorities are struggling with recruitment and workload.

“I have seen estimates on the restoration potential using very high figures, whereas estimates on the damage seem to use low figures,” said Bain.

“This illustrates there’s not consistency in carbon numbers and impacts, and it’s left to the developers’ judgement – there needs to be much clearer guidance on which numbers are used.”

He warned that “otherwise it is potentially possible to inflate numbers for restoration and reduce numbers for damage.

“I’m not saying any developer has done that. I’m saying the risk is there because we haven’t got standardised numbers.”

Policy needs to catch up with science

A Scottish Government spokesperson said they “note the limitations” of the payback calculations, but said the calculator still provided “the best available means” to get figures in a “consistent and comparable format”.

The government recognised the “need to strike a balance between maximising deployment to reach net-zero targets, while protecting our local communities, priority peatlands, natural heritage and scenic landscapes, while delivering economic benefits to Scotland,” the spokesperson said.

So-called shallow peat – just 30cm deep – contains the carbon equivalent of rainforest. “You wouldn’t think about removing a hectare of rainforest,” said Dr Chico. “But it’s the same amount of carbon – and the rainforest won’t grow more, while the peat will accumulate more over time.”

Chico said he’s frustrated and wants policy to catch up with science. “The best we can do is collect data and hopefully in 100 years’ time, somebody has that data and can say ‘this isn’t going well’.

“Obviously we already have indicators telling us that it’s not going in the right direction.”

As Scotland prepares to host world leaders in the COP26 climate summit, the Scottish Government has made clear that the onshore wind boom is here to stay – for another decade at least.

“It’s really ironic that we’re putting a lot of money into restoring heavily degraded peatlands,” said Chico.

“Then you go to a natural peatland in the Shetland Islands – and do the opposite.”

Wind farms on any depth of peat “make less and less sense” as the energy grid is decarbonised, said Smith, adding that bogs in a natural state must be protected.

“That’s the bottom line”, she said. “Pristine peats are an important resource for the world, both in terms of biodiversity and carbon storage, and have a huge amenity value.

“Once we’ve destroyed them, we won’t have them anymore.”

Become a member of Shetland News

Shetland News is asking its readers to consider paying for membership to get additional perks:

- Removal of third-party ads;

- Bookmark posts to read later;

- Exclusive curated weekly newsletter;

- Hide membership messages;

- Comments open for discussion.

If you appreciate what we do and feel strongly about impartial local journalism, then please become a member of Shetland News by either making a single payment, or setting up a monthly, quarterly or yearly subscription.