Viewpoint / ‘We are blessed with abundant potential at a time the world needs it most’

Daniel Gear, who is originally from Shetland but based in Aberdeen, works in the analysis of global energy sectors, and sits on the board of the UK statutory skills and training body for Engineering Construction.

He is currently providing advisory services to early-stage industrial-scale projects related to carbon capture and storage, and hydrogen production in the UK.

Gear said he has “recently picked up on a fair bit of misinformation in circulation” around the Viking Energy wind farm and the interconnector.

In this Viewpoint he shares why he thinks the interconnector cable between Shetland and the Scottish mainland, and Viking Energy, are important projects.

I originally composed this letter for Facebook with the intention of promoting discussion around the benefits of the wind farm, the associated interconnector, and why the two an important part of the bigger global energy picture.

After a lot of encouraging discussion, and after reading some of the recently published letters to Shetland News, including Shannon Leslie’s excellent contribution, I thought I would share my viewpoint on why I think the project makes sense.

I’d like to start by discussing the project in the context of climate change, which means taking a global view first, then a national view, then a local one.

Climate change is real. The IPCC [Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change] states with “high confidence” that the burning of fossil fuels was responsible for the contribution of 78 per cent of total global GHG [greenhouse gas] emissions between 1970 and 2010.

Furthermore, there is high confidence that half of the total CO2 emissions from the previous 260 years have occurred in the last 40 years alone. The connection between the increasing use of fossil fuels, the associated CO2 emissions and the increasing atmospheric concentrations of CO2 is well understood.

Become a member of Shetland News

The other area that is well understood is how this increasing concentration of CO2 affects the global average temperature. We’re currently at about 415ppm of atmospheric CO2 concentration, which will likely raise average temperatures by around two degrees on pre-industrial levels, if we can get our emissions under control.

But two degrees is an abstract concept, how many people will actually die because of that level of warming? The answer is about a quarter of a million people per year on average between 2030 and 2050 as a direct result of climate change, and indirectly about 10 per cent of the total maximum forecast global population spread over the next two centuries.

When you work the numbers back, you find that the future death rate for the two degree warming scenario is about one person per 1,000 tonnes of CO2 emitted today.

Currently, over four billion people are deemed to be vulnerable to the primary and secondary socio-economic effects of climate change, with the majority of these people living in Sub-Saharan Africa, South and Southeast Asia, Latin America and small developing island states, and are often heavily reliant on farming for their livelihoods.

The reason these people are deemed vulnerable is due to a vicious cycle of climate effects: rising temperatures compound existing fresh water shortages; fresh water shortages reduce arable land; less arable land reduces food security; lack of food security and income from crops results in increasing health problems, which further diminishes the ability to be economically productive, and places an additional burden of care on people who are already severely economically strained.

This vicious cycle then acts as a driver for the migration of populations, resulting in spreading socio-economic unrest, driving further scarcity of resources as the populations move and put strain on the resources of adjacent regions.

Now, the thing that is most unjust about this, is that the people who are most affected, are the people who have contributed least to the drivers of the problem.

When delivering the Royal Economic Society public lecture in 2007, Nicholas Stern described climate change as being “a result of the greatest market failure the world has seen. […] The problem of climate change involves a fundamental failure of markets: those who damage others by emitting greenhouse gases generally do not pay”.

In economic theory, the term for this effect is a ‘negative externality’ – it’s where a situation arises in which third parties, who are not directly involved in the production or consumption of a product are adversely impacted by others producing or consuming the product.

Make no mistake, in Shetland we have been beneficiaries of this negative externality for as long as we’ve benefitted from the production of hydrocarbons, and indeed their consumption.

The last IPCC report suggested we have about 10 years at the current rate of global emissions before exceeding the carbon budget that is set to prevent the worst effects of climate change.

It’s possible we’ve already crossed that invisible threshold. Similarly, the International Energy Agency’s ‘Tracking Power’ report from last month shows that the power sector emissions declined by 1.3 per cent last year, but these emissions need to decline by four per cent average per year to 2030 to keep us on track with the Sustainable Development Scenario (which is aligned to delivering the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals).

I’ve only picked two reference points here for brevity, but the key message is that we are not currently on track to effectively deal with the existential threats posed by climate change.

The fundamental issue is that when you look at the whole world energy system, there are simply not enough clean energy or carbon negative projects currently planned or in development to help us mitigate the worst effects of climate change. This is a huge threat, and not just to poor people on distant shores, but soon to Shetland in myriad ecological ways.

The result of all this is an urgency to pull the best mitigation levers we have, and try to walk the finest of lines between doing this as quickly as possible, with as little impact on people as possible (particularly those already in extreme poverty). We have two real-world counterbalances to help us walk that finest of lines – the available technology today, and the project economics today.

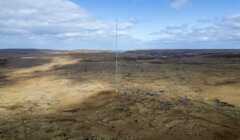

Shetland is famous for having the best wind resource in Europe – we are blessed with an abundance of renewable potential at a time when the world needs it most. Looking at wind, there are essentially two technology options available: offshore and onshore. Unfortunately, the reality of the project economics today is that the Levelised Cost of Energy (LCOE) is, at a minimum, 50 per cent higher per MWh for offshore wind, than onshore wind.

This LCOE relationship will flip in between 10 and 20 years as the offshore turbine capacity grows ever-larger, but it’s not the case today. This means that onshore wind is the only viable option for a project that can also support a grid connection, and still meet the required rate of return.

It’s absolutely right that the carbon payback period should be scrutinised in the context of peat disruption; however, it’s worth treading with caution here to avoid some of the misinformation I’ve seen being circulated.

The report and the associated models that suggest a carbon payback period well within the operational life of the windfarm stands up to due diligence, and the authors have followed best practice in an admittedly nascent field. However, it’s not enough to assess the payback period of the wind farm in isolation – we need to look at the huge carbon offset potential that the associated interconnector unlocks too. More on that below.

The other thing Shetland is famous for is our heritage on the global oil and gas stage. So why is Shetland advantaged in this regard? Well firstly, we have an abundance of existing oil and gas pipelines and infrastructure, and some of the potentially longest lived and sizeable remaining oil and gas assets in the UK to the East and West of Shetland.

That’s important for a couple of reasons. Firstly, we need to do something that might seem a bit counterintuitive in the context of climate change – we need to produce more hydrocarbons domestically. The reason for this is that the UK is currently a net-importer of hydrocarbons.

The act of importing a barrel of oil equivalent, either by pipeline or tanker adds to the carbon emissions associated with the production and consumption of that barrel of oil.

In essence, we need to reduce our reliance on imports by increasing the amount of domestic production (therefore reducing the average CO2 per BOE consumed), whilst simultaneously undertaking measures to reduce our overall hydrocarbon consumption at a national level.

Secondly, the fact that Shetland has existing infrastructure is hugely important, and in fact this gives us an advantage over a great many other places in the world.

To borrow an example of why this is important from the Acorn CCS & Hydrogen project in Aberdeenshire – they’ve calculated project savings of around £750 million by being able to re-use existing infrastructure, including pipelines, facilities and utilities at St Fergus. The fact that Shetland is surrounded by platforms, pipelines, depleted reservoirs and existing terminal infrastructure means we are well placed to redevelop this for clean energy purposes. And that’s before we even acknowledge the fact that we have a deeply skilled resident workforce, with a pressing need to secure future opportunities.

Now this is where the interconnector could open up a world of strategic, clean, long-term opportunity for Shetland, and crucially, send Shetland’s contribution to the mitigation of climate change into the global major leagues.

Let me be totally clear; the Shetland Energy Hub could be the most important long-term project for Shetland in our collective lifetimes. And that can only happen with the interconnector, which can only happen with the wind farm.

So what potential does the interconnector unlock?

- We could support the electrification of onshore and offshore asset power generation. That could cut the operational emissions of these assets by over 60 per cent which could support the abatement of as much as two million tonnes of CO2 per year.

- The lives of these assets could be extended through reducing their operational emissions costs (among other life-extension measures), which would support the drive to increase the ratio of domestic hydrocarbon production described above, and blue hydrogen production described below.

- Offshore wind should be developed and ‘plugged in’ as the LCOE meets onshore wind values in the future.

- The clean power generation capacity required for CO2 separation, conditioning and compression processes would be readily available; by using existing pipelines and depleted reservoirs, emissions could be point source captured from Sullom and the Gas Plant (abating in the region of 350,000 tonnes of CO2 per year).

- Other CO2 capture systems could be built in as the technology matures, such as Direct Air Carbon Capture Systems.

- The clean power capacity would be readily available to run steam methane or auto thermal reforming (SMR / ATR) processes to produce blue hydrogen from natural gas, and could sequester the resulting CO2 through the existing infrastructure in the same way as described above.

- Green hydrogen could be produced as an energy carrier using electrolysis when there is an abundance of cheap available energy.

- Industrial quantities of ammonia could be produced which could be used to transform the horrendously polluting shipping industry in the North Sea Basin into a new clean sector.

- The interconnector will unlock a sustainable long-term future for the residents of Shetland. High value, exportable expertise could be developed in clean energy systems, and we could take advantage of the opportunity to generate significant return for the Shetland economy.

- From Shetland, up to five million tonnes of CO2 could be abated per year by this time in two decades, thanks to the potential that the interconnector unlocks through the projects described above.

In Shetland, we have punched above our weight in the oil and gas industry for more than four decades, but during that time the molecules produced through our shores have done disproportionate harm for the benefits we’ve reaped.

Now, we find ourselves once again in possession of a commodity that the world needs. But this time we have the opportunity to be a clean energy leader on a global stage, with the highest CO2 abatement figures per head of population in the world; remember what I said about the human cost of these emissions – we would effectively go from being responsible for the most climate related deaths of any region in the UK per resident, to being responsible for the most lives saves per resident, in the world. That is within our gift.

We can develop a world leading clean energy hub and do disproportionate good because of it, and the community will benefit from it over generations. But there is a very short window of time, and it’s only possible with the interconnector, which is only possible with the wind farm. So that is why the project makes sense.

Become a member of Shetland News

Shetland News is asking its readers to consider paying for membership to get additional perks:

- Removal of third-party ads;

- Bookmark posts to read later;

- Exclusive curated weekly newsletter;

- Hide membership messages;

- Comments open for discussion.

If you appreciate what we do and feel strongly about impartial local journalism, then please become a member of Shetland News by either making a single payment, or setting up a monthly, quarterly or yearly subscription.